“We were given a toilet under the scheme, but the pit is broken, so we don’t use it.”

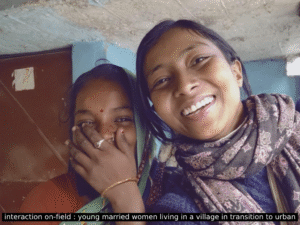

These were the words of a woman I met in rural and peri-urban neighbourhoods transitioning into urban spaces in a tier-2 city. For her, that broken toilet is the problem, one that affects her daily, privately, and publicly.

It was built under the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM Gramin and Urban), a national campaign aiming to eliminate open defecation in India by constructing over 100 million toilets, primarily through funding Individual Household Latrines (IHHLs). These were supported by a monetary incentive that covered both the superstructure (the toilet) and the containment system (soak pits or holding tanks). But these pits may break, or fill up and fail. Since the maintenance wasn’t factored into the design or the budget, what remains is a locked door – and a practice that silently continues in fields and corners.

Why can’t we have a system that efficiently carries all sewage for treatment, instead of holding it locally and polluting our planet in the process? Is it a lack of sewage treatment plants, or is it the sanitation infrastructure that hasn’t kept pace with the speed of urbanisation? The toilet may exist, but the sanitation does not.

In another conversation, a woman told me, “There is no dustbin in my lane, the closest one is always overflowing. So I dump the waste in the lake behind.” She’s not unaware. She knows it pollutes the water, but when your home is small, filled with children, and the municipal garbage pickup doesn’t reach you, what are your options?

In the city where I’m working alongside an NGO, very few households receive door-to-door waste collection. Most report dumping waste in vacant lots or water bodies. In most cases, this isn’t due to apathy or lack of awareness. It’s a systemic absence of services, bins, and last-mile infrastructure. This Tier-2 city is still forming. This is both a challenge and an opportunity to build better, and no one actor can do it alone. Government bodies, CSOs, private players, data experts, academicians, and most importantly, local communities must come together in dialogue and collaboration.

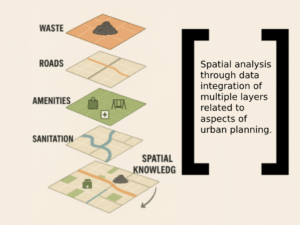

What we see as problems – a broken toilet, a garbage pile, or a mosquito-infested drain – are just symptoms. The real causes often lie deeper: fragmented service delivery, missing last-mile connections, outdated data, and a lack of coordination across urban departments. Schemes are planned but not always grounded in real use cases. Data may be collected, but it rarely loops back to inform budgets or decisions. Initiatives exist, but often float disconnected from one another and from people’s lived experiences.

We must peel the onion, the problems are layered, and unless we trace and understand the relationships between these layers, we risk applying surface-level fixes to deep-rooted, foundational design failures. If we want systems that last, we must first see what lies beneath, what exists to design systems and build urban spaces that are based on evidence and built to adapt.