In earlier articles, we examined the range of complaints received by the Gurugram Police—from domestic disputes to street harassment—and how these cases are prioritised. However, addressing safety requires more than reactive policing; it demands a deeper look at the structures that shape our cities. Urban planning, often seen as neutral, is in fact a powerful tool that can either reinforce or reduce vulnerability, especially for women.

Gurgaon is often hailed as a beacon of modern India, with its gleaming towers and global business parks. Yet, beneath this image lies a city built more for cars than people, more for business than inclusion. Wide highways, gated communities, and privatised public spaces dominate the landscape, leaving few opportunities for accessible recreation, spontaneous social interaction, or community bonding, highlighting a critical lack of inclusive design in the urban fabric.

This disconnect stems from the fact that urban planning has historically been considered gender-neutral, often, in practice, gender-blind. Cities have long been designed around the needs of an able-bodied male commuter, with little consideration for those who navigate urban spaces differently. In Gurgaon, for example, the infrastructure often fails to support women’s mobility, safety, and comfort, particularly for those juggling work, caregiving, and daily errands. As a result, the design of the city overlooks the complex and multifaceted ways in which women experience and move through urban life.

Global research backs this up. A 2021 UN Women report found that women are less likely to use parks, streets, or public transport at night when spaces are poorly lit or sparsely populated. In Gurgaon, the situation is stark. A 2021 Safetipin audit revealed that 35% of streets lacked adequate lighting, and 37% of women reported feeling unsafe in public spaces after dark.

But safety is about more than lighting. A 2011 study by UN Women and Jagori highlighted that women feel safer in environments with “eyes on the street,” accessible transport, and clean, usable public toilets. Gurgaon performs poorly on several urban design fronts, with scarce public toilets for all genders, broken or missing sidewalks, and a strict separation of residential, commercial, and recreational zones that makes walking both inconvenient and unsafe.

Transport is another key barrier. According to NFHS-5, only 32% of women in Haryana feel safe using public transport alone. Gurgaon’s unreliable public transport system leaves women dependent on expensive private modes or limits their movement altogether.

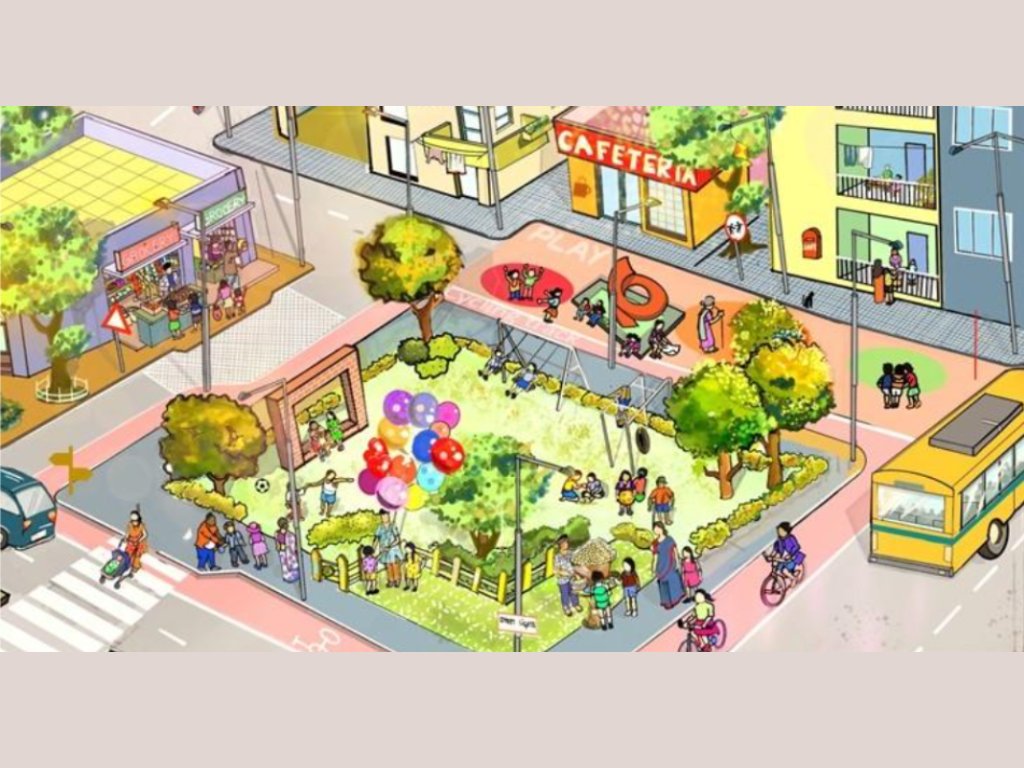

Even public spaces reflect gendered exclusion. Basic amenities like benches, shaded areas, childcare facilities, and toilets are rare. As a result, private malls, surveilled and perceived as safer, have become the default gathering spaces for women. But safety should be a public right, not a privilege confined to private spaces.

Various organisations and urban researchers, in collaboration with local stakeholders, have mapped unsafe zones and proposed gender-sensitive interventions ranging from improved street lighting to safer pedestrian pathways. Yet, in the absence of coordinated implementation and sustained political will, these efforts often remain fragmented and fail to bring systemic change.

What’s needed is a fundamental shift in how cities are designed. Gender-sensitive urban planning must become the norm, not the exception. This means involving women in planning decisions, conducting gender impact assessments, and prioritising infrastructure that reflects the routines and realities of all residents.

Urban safety isn’t just about preventing crime—it’s about enabling freedom, participation, and dignity. A city built with women in mind is ultimately a city that works better for everyone.