As I deepen my understanding of spatial data and how it can illuminate service gaps, I’ve also strengthened my belief that data alone doesn’t build better cities. It needs something more, something human. Planning becomes truly powerful when we ask, Whose voices are missing from this map?

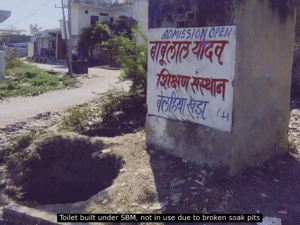

My curiosity and work of interest including being a UCAN fellow, is shaped by a desire to create sustainable and inclusive impact, and as I’ve interacted with communities in different urban settings, one truth has become clear, the most vulnerable are rarely part of the conversation, even though they are most affected by urban failures. While many government schemes target these groups, like Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), gramin as well as Urban for housing or National Urban Livelihoods Mission (NULM) for livelihoods, the ground reality is that the intended most vulnerable beneficiaries are often left behind, for an instance, many villagers on ground mentioned applying for PMAY and having no response yet, there are other reasons too, like lack of awareness, cumbersome documentation etc. These aren’t failures of policy but of process, gaps that widen when people are treated as recipients, not participants.

Women, in particular, experience cities differently. In one neighbourhood I visited, a group of women spoke about avoiding going out after dark, lack of anganwadi and school for their children, or walking long distances to reach the nearest PHC (Public Health Centre). Their stories are not anomalies, they are daily patterns. Their needs are critical to designing responsive infrastructure, yet their input rarely shapes the final blueprint. This is why community-driven research matters. When citizens are invited into the planning process

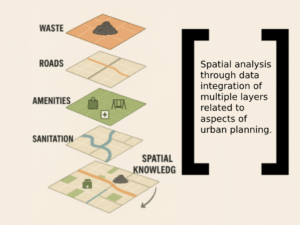

This is where organisations like Shelter Associates offer a compelling model. leveraging household-level spatial data, not just to map, but to listen. Their teams engage directly with communities. The result is not just a database, but a deep, actionable understanding of who needs what, where, and why. Their approach has translated into many successful projects with community involvement, planned with data that includes not only geo-spatial gaps but also social and cultural context. But for planning to be meaningful, it must be institutionalised into government processes formally and not as an option.

Governments must move beyond token consultations to embed community voices into every stage of the development cycle, from data collection and scheme design to monitoring and evaluation. As someone committed to inclusive development, I, too, believe this is where the real transformation lies because cities aren’t just made of roads and buildings. They’re made of people. And unless planning is done with them, we risk building systems that fail the very people they’re meant to serve.