Urban planning in cities like Gurgaon has long been shaped by the priorities of a narrow group, often overlooking the lived experiences of half the population. To create safer, more inclusive urban environments, we must center women not just as users of the city, but as planners, decision-makers, and co-creators.

Urban planning isn’t neutral; it reflects the priorities of those who design it. When planning is primarily shaped by a limited demographic: often male, middle-class, and able-bodied, the resulting infrastructure may unintentionally reflect only a narrow set of experiences and needs. Including women in planning ensures a wider lens, one that takes into account caregiving responsibilities, safety concerns, and the need for accessible public amenities.

Including women in planning ensures a wider lens, one that takes into account caregiving responsibilities, safety concerns, and the need for accessible public amenities. Understanding how different groups interact with urban spaces is key to designing cities that serve everyone effectively. According to the OECD, women in India perform nearly 10 times more unpaid care work than others, averaging over 5 hours per day. These care responsibilities structure how and when women use the city, particularly in ways that are time-sensitive, multitasking, and reliant on public infrastructure. Their urban routines involve multiple short, chained trips, often on foot or using public transport. A study by the ITDP (Institute for Transportation and Development Policy) found that women in Indian cities take 45–80% more short trips than men, often during off-peak hours and across multiple destinations. This kind of travel is poorly supported by cities designed for single-point commutes. Yet urban design still prioritises wide highways, private vehicles, and office-centric zoning, neglecting the needs of citizens who depend on walking, cycling, or public transport. In Gurgaon57% of women in Gurgaon report feeling unsafe in public spaces after dark (Safetipin, 2021); highlighting how current urban design continues to neglect the lived realities.

Moreover, just 18% of women in urban India participate in the formal workforce (PLFS, 2022), a number shaped not only by economic factors but also by the built environment. Poor transport options, long commutes, and unsafe public spaces restrict women’s access to jobs, education, and health services.Additionally, inadequate road maintenance further compounds these challenges, making mobility especially difficult for those with specific needs, such as pregnant women or individuals with health conditions.

Despite the clear need, women’s voices remain underrepresented in planning decisions, as municipal bodies often lack gender balance and community consultations are frequently scheduled in ways that unintentionally limit the participation of working women and caregivers, resulting in their lived experiences being overlooked as a vital source of insight.

Planning data is also not gender-sensitive. Without disaggregated data on how women move, work, and interact with the city, policies fail to respond to real needs.

To make participation of women more meaningful there are a set of potential recommendations based on my learning.

- First, planning bodies must include women at all levels from ward committees to development authorities. This inclusion must be intentional, not tokenistic. Training, mentorship, and leadership development programs are essential to empower women to take up space in technical and policy domains.

- Second, public engagement must be designed with access in mind. Holding consultations at NGOs, health centers, or near schools—and at times suitable for women—can increase participation. Participatory tools like safety walks, pioneered by Safetipin and Jagori, have already helped women influence planning decisions in cities like Delhi, Bhopal, and Bangalore.

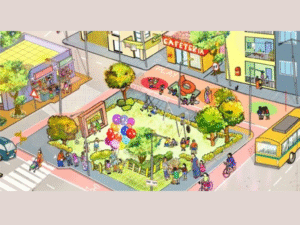

- Third, cities must adopt the lens of a child-friendly city—a planning framework that ensures public spaces are safe, inclusive, and accessible not only to children, but to caregivers, the elderly, and the disabled. Planning for women often means planning for families, communities, and the most vulnerable.

We have to understand that A City that Listens is a City that Protects.

When women help shape cities, the impact goes far beyond safety. Inclusive planning builds social cohesion, increases participation in public life, and results in cities that are more livable for everyone. As Gurgaon and other Indian cities continue to grow, they must move from designing for efficiency and profit to designing for dignity, inclusion, and care. And that begins by putting women at the center of planning—moving them from the margins to the map.

As I continue my journey with U-CAN and Safetipin, we’ll explore how gender-disaggregated data can drive more equitable and responsive city design.