As I reflect on this journey, from witnessing urban failures to peeling back their layered causes, exploring the potential of data and the importance of community voice, one truth remains: cities are not built by plans alone. They are shaped by people, communities, governance and decisions that often unfold in silos. When these elements are brought together through co-creation, something shifts. We begin to see the possibility of cities that are not just functional, but inclusive, resilient, and rooted in the people who live in them.

In my work, driven by the pursuit of learning to create impact, it has become increasingly clear that there is no one-size-fits-all model for planning. The most effective approaches are those that are context-specific and multi-actor, and participatory. When communities, local governments, private actors, and civil society collaborate, bringing their insights and resources to the same table, we can aspire to move closer to designing cities that work for all.

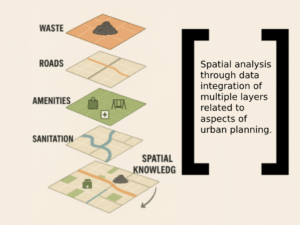

I’ve seen this at work, as the Civil Society Organisation (CSO) I work with prioritises grounded planning. Their approach begins by collecting spatial data on sanitation, housing, and waste management, etc, especially in informal or under-served settlements and household-level data, but data isn’t an end in itself, Shelter associates and other U-CAN members committed to inclusive urban change, actively engage with communities, listening to their needs, challenges and bringing these insights into conversation with municipal authorities, enabling institutional capacity at the local level. This results in collaborative solutions that not only meet technical specifications but also reflect real demand and social ownership. Their model shows us what’s possible when we plan with precision and participation.

When ward-level data is made accessible and actionable, it enables more targeted and equitable interventions, budgets and funding can be allocated and prioritised more effectively, and Government plans, schemes, and initiatives also gain renewed relevance when they respond to the actual needs of a growing urban space.

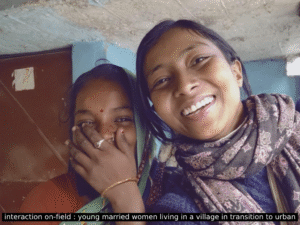

Tier II and III cities, on the cusp of urbanisation, have a rare chance to define their own trajectories, grounded in local context rather than inherited templates from larger metros. As these areas evolve, the focus should not be on replacing traditional systems, but on integrating them. There is immense value in preserving vernacular architecture, enhancing existing construction techniques, and sustaining livelihoods that have long supported these communities. Development here can be a process of layering, where new infrastructure and services grow organically from what already exists, rather than being imposed externally.

These transitioning cities also offer fertile ground for building governance models rooted in participation. Community institutions already embedded in social life can be mobilised for decision-making on planning, budgeting, and public services. This collaborative approach, if embedded early, can redefine urban governance, not as a top-down mechanism but as a shared process. With thoughtful planning and inclusive engagement, these cities can become living examples of how urban growth can be equitable, responsive, and deeply connected to place.