Ajmeri Gate- Gateway to Jaipur’s Heritage. Photo credit: Author

The beautiful city of Jaipur has always been a major pin on my life’s map. Even though I grew up in Delhi, Jaipur was where my favourite cousins lived, and where I spent nearly every summer, winter, and Diwali break for 17 years. I vividly remember strolling through the bustling streets of Bapu Bazaar and Chaura Rasta with my family to enjoy the amazing street food as a child.

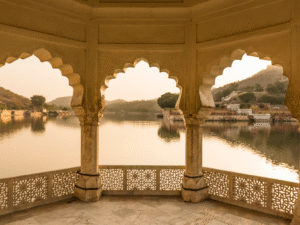

Later, when I pursued my bachelor’s degree here between 2008 and 2013, commercial complexes like Gaurav Tower and Pink Square Mall were the most popular hangout spots for our college group. In 2020, marriage brought me back to Jaipur for good. I was excited to show off the city to my partner—after all, I had spent more time here than he had. But to my dismay, our tour ended with the familiar heritage sites like Amer Fort, Hawa Mahal, and Jal Mahal, along with a few older hangout spots I remembered from college.

Many of these public spaces were poorly maintained and felt outdated. Yet they remained overcrowded; not because they were inviting, but because people, especially youth, had few other options. I struggled to find inclusive, well-designed, accessible, and safe public spaces in the city. When I asked around, the most common suggestions were indoor venues like restaurants, cafes, and lounges, which have now become the go-to spaces for Jaipur’s younger crowd.

The Pink City, celebrated globally for its historic beauty and landmarks like the City Palace and vibrant bazaars, seems to be stuck in time. It was unsettling to realise that the city hasn’t kept pace with the evolving needs of its people, especially the youth. Today, every fifth person in India is an adolescent (10–19 years), and every third is a young person (10–24 years). Inclusive public spaces, as essential parts of urban infrastructure, are vital for youth to explore the world around them, become independent, and engage in activities that support their physical and mental well-being.

In the absence of safe, inclusive, and accessible spaces like parks, plazas, or open squares, the city’s youth are increasingly drawn to indoor spaces to unwind and interact. But these come with barriers: cost, social exclusion, and limited opportunities for physical activity. Unlike free, open-air public spaces, they are not designed to be truly accessible or empowering. For any city that hopes to grow inclusively, investing in vibrant outdoor spaces that belong to everyone is essential. These spaces are not just leisure spots, they are central to the social and cultural life of a city.

I got the opportunity to join the U-CAN Fellowship and work with WRI India on a project focused on developing public spaces for adolescents through a tactical urbanism approach. This work gave me a new window into the issue of inclusive public space in Jaipur. I had the chance to engage with different neighbourhoods and communities, and these interactions were eye-opening.

Many adolescents from economically disadvantaged backgrounds rely solely on community parks or school-adjacent grounds for recreation. For them, these public spaces are their only chance to play, interact, and just be themselves. Their desire for dynamic, safe community spaces came through strongly, along with concerns around mobility, safety, and basic amenities. These conversations reinforced a powerful truth: urban environments are not neutral. They either enable or exclude participation, especially for marginalised groups.

This experience has made me realise just how complex it is to create public spaces that truly respond to peoples lived realities. Every conversation, every walk through a neighbourhood, has revealed layers of urban life that often go unnoticed in planning processes. I’m beginning to see patterns, but the intersections of gender, age, safety, and space remain deeply layered and nuanced.

At this point, rather than rushing to solutions, I feel the need to pause. To sit with the problem. To make space for its contradictions. And most importantly, to listen—really listen—to the many voices shaping our cities.

Hawa Mahal- Where the Winds Tell Stories. Photo credit: Author